As the market for chips in cars grows, so does the amount of sensor data that needs to be processed.

All kinds of chips are going into driver-assisted and autonomous cars. On one side are arrays of sensors, which are generating huge amounts of data about everything from lane position and proximity to other cars to unexpected objects in the road. On the other side are the chips required to process that data at blazing speed.

As the market for PCs and mobile phones enter slower-growth phases, automotive has emerged as the next big market opportunity for chipmakers because it leverages technologies already developed and silicon-proven for both of those markets. That includes ASICs, CPUs, FPGAs, GPUs, MCUs, DSPs and an assortment of memory chips. It also includes mobile processors that ultimately will put 5G into the reach of drivers.

The stakes in this game are enormous. Qualcomm’s $47 billion proposed acquisition of NXP Semiconductors— the world’s largest supplier of automotive chips after buying Freescale for $11.8 billion in 2015—is a case in point. So is Samsung’s $8 billion acquisition of Harman, a tier-one auto supplier. And companies such as Renesas (which just completed its $170 million acquisition of Intersil), Infineon, STMicroelectronics and Texas Instruments are all pouring money into this field to carve out a position.

San Francisco-based Grand View Research forecasts the worldwide automotive semiconductor market will be worth more than $35 billion by 2022, with a compound annual growth rate of 10% over the next 5 years. But the numbers also are deceiving. Technology designed into cars historically has provided a multi-year revenue stream for companies that develop the technology. So while the volumes are still higher in the mobile market, for example, chips in mobile devices are swapped out as frequently as every year. Automotive designs can last several times as long, and sometimes even longer than that.

“What we’re seeing now is an evolution or a tipping point in the industry where the traditional automotive electronics model is evolving and changing,” said Michael Hendricks, director of the Automotive Business Group within Intel’s Programmable Solutions Group. “The background comes from a history of ASICs and MCUs. Now we are at the point of processing requirements to achieve something like fully automated driving are really forcing an order of magnitude step function up. Therefore, you’re starting to see some more unique capabilities come into the fore.”

Behind those capabilities are a mix of high-performance CPUs, FPGAs and application-specific processors, rather than just one type of chip, and a slew of other types of chips. “In 2015, a mid-range sedan had approximately 30 electronic control units,” said Paolo Piacentini, applications engineer manager at Kilopass Technology. “Multiply that 30 by 66 million, the global number of passenger vehicles sold in 2015, and you have nearly 2 billion ECUs manufactured and sold in 2015. Each MCU embeds programmable eNVM of some kind, especially flash but also antifuse OTP. The eNVM are necessary for storing application codes, OS images, BIOS, security keys (for software updates), secure ownership (owner ID), calibration parameters and configuration settings for the hosting ECU. As a result the shipment volumes for OTP in automotive is considerable.”

So are the volumes of of ASICs and MCUs. “The pace that the industry is going to need to move in the months and years moving forward, the types of architectures that we’re likely to see in these very advanced systems are going to be heterogeneous or a mix of different kind of chip architectures,” said Intel’s Hendricks. “The autonomous vehicle effectively is going to be generating a massive amount of data — something on the order of around 4 terabytes of data per day by 2020. Feeding that cycle of growth between data center, the servers, the cloud, and also those connected devices like the automobile, FPGA and memory play a huge role in that overall strategy. It’s having high-bandwidth memory available for the type of processing horsepower that’s required directly in the vehicle, and then pumping all that data back in the cloud for training, reprocessing, and then sending that trained data back to the connected devices.”

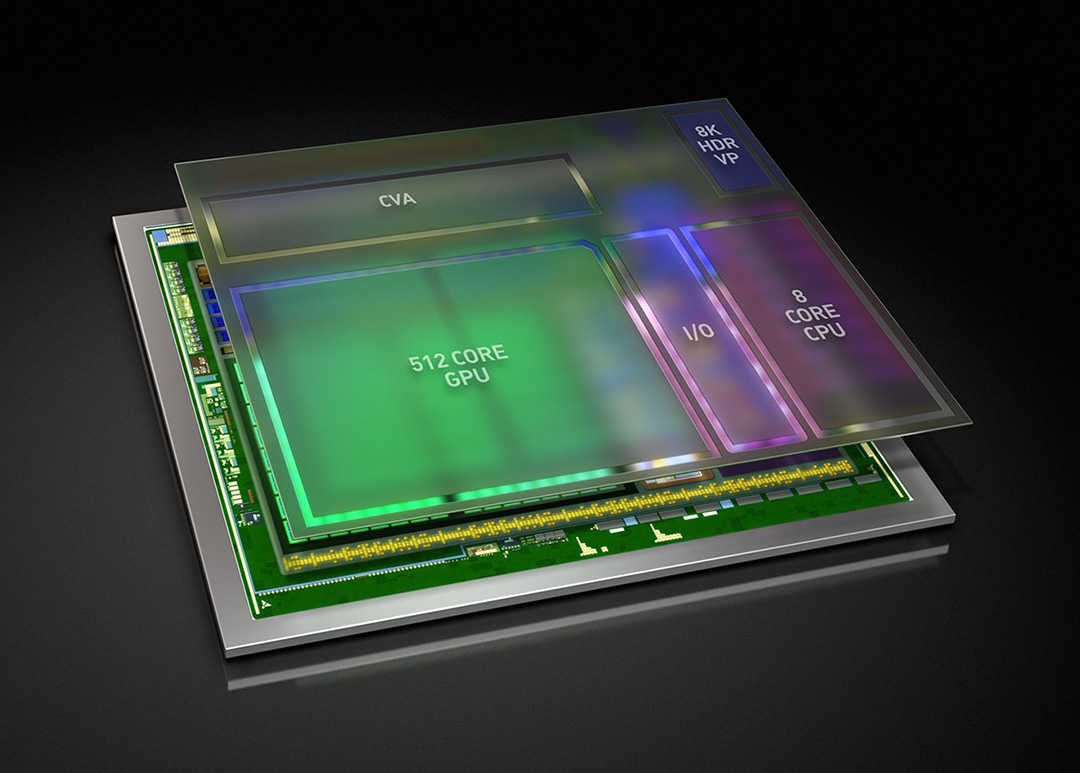

The starting point for many of the players in this market are their existing strongholds. For Intel it is CPUs. For Nvidia the starting point is the GPU, which is apparent in its new Xavier SoC.

Fig. 1: Nvidia’s high-speed Xavier SoC. Source: Nvidia

Terabytes per gallon

In many respects, the future of automotive design is a big data problem on wheels. Vehicles at present can contain 150 or more electronic control units (ECUs). In the next decade, industry experts say that figure could shrink to 50 ECUs through sensor fusion and other integration measures.

These sensors generate huge amounts of data, which needs to be processed quickly to avoid injuries or other mishaps. This is true for driver-assistance features, such as lane-departure and front-collision warnings, as well as for backup cameras. And the amount of data that needs to be processed in autonomous vehicles is even higher, because that data determines whether a car needs to stop, slow down, change lanes or avoid objects. Things that seem simple to a person, such as a waving branch or blowing rain, can be very confusing to an autonomous vehicle. It requires a huge amount of data to be collected, which then has to be relayed back to the central brain of the car in real time.

“The key is bandwidth,” said Wally Rhines, chairman and CEO of Mentor Graphics. “You can’t get enough of it. And if you can’t solve that, you can’t get to the central CPU. If you’re driving on the Autobahn at 150 miles per hour, how do you get an image of a dog in time?”

Where a car differs from other big data problems, such as a financial trading floor or an online shopping site such as Amazon, is that data comes from a variety of sources and in a variety of formats—LiDAR, radar, image sensors for the embedded vision systems, as well as vibration sensors, accelerometers and gyroscopes.

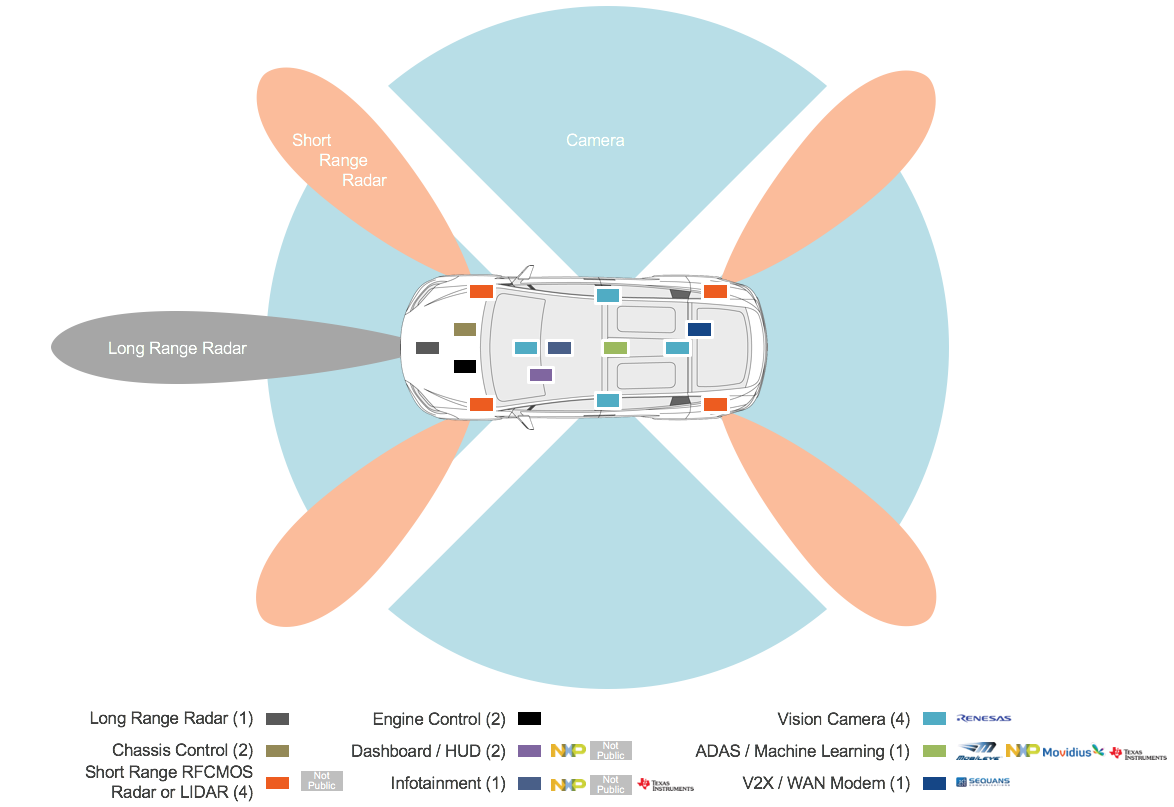

Fig. 2: Number of sensors generating data. Source: Arteris

As such, being able to process that data quickly requires a more complex architecture than a standard server chip can handle.

Improving data flow

In a car, this becomes an on-chip and an off-chip data logistics problem. Moving large quantities of data around a car is slower than processing the data at a sensor, for example. So whatever data can be pre-processed locally will speed up the flow of data because it will result in less data movement.

While much of the work being done today is focused on a central brain in cars, ultimately the compute model will likely be more distributed.

“It’s probably going to be a hybrid system,” said Jinesh Jain, supervisor for advanced architectures in Ford’s Research and Innovation Center in Palo Alto. “We have to be able to grow one into the other. We have to be able to justify the cost. It has to meet the performance to do that. And as these applications get stricter, that’s the kind of reliability we will have to meet. There are so many ways that’s being looked at.”

That’s one of the problems, too. Everything in this market is in flux. The first step is to understand the capabilities of the individual components and what they are capable of, which is difficult to do when everything is evolving or completely changing.

“We need standards for how to connect to the brain, and we need separate data standards,” said Kurt Shuler, vice president of marketing at Arteris. “There will have to be a lot of processing on the edge. Individual sensors will have to have their own processor and abstract knowledge from the data. The bandwidth is not there to handle all of the data. It’s a divide-and-conquer strategy.”

This determines how much on-chip and off-chip memory is required, and whether a system needs cache coherency across multiple processor cores, for example. So far, there is no clear direction here.

“With self-driving cars, you can expect to see additional demand for memory that is disconnected from the driving,” said Steven Woo, distinguished inventor and vice president of marketing solutions at Rambus. He added that DRAM is a logical choice because of cost and speed, but noted there is room for other memory types, as well.

But even the protocols through which data moves are changing.

“There are a lot of protocols because you need to maintain backward compatibility,” said Bernie DeLay, group director for verification IP at Synopsys. “And automotive moves slowly because of safety considerations. You have to plan for single event upsets and other issues defined by ISO 26262. But you also need to have enough speed to memory, which is why we’re seeing the PCIx protocol being used. And the memory size may not be large enough, so you need cache coherency across multiple chips. This was being done ad hoc, but the latency was too high. So now there are new cache protocols being used.”

Where else does the data go?

It’s easy to forget the original concept behind autonomous and driver-assisted vehicles, which is that cars need to be connected to the cloud, as well. The trend is to extract more data from all technology as it is deployed and ship it off to data centers.

“If you look at a lot of these vehicles that have this [driver assist technology] already, they’re getting data streamed back to factories on effectiveness of the models, so they’re getting improved all the time by real-world testing,” said Luke Schreier, director of automated test marketing at National Instruments. “The same goes for wireless carriers. They can identify where poor performance is in the networks based on calls dropped and everything else.”

This adds to the flow of data in cars, and introduces yet another level of data that needs to be addressed in designs. While security is critical within the vehicle, the likely avenue for hacking into cars is outside the vehicle.

Nor is it just about the data being processed inside the car. The entire design side adds another wrinkle that needs to be considered because in automotive design, technology sticks around a lot longer than in mobile phones.

“Design approaches are being introduced that are new to the traditionally small and autonomous AMS design teams,” said Ranjit Adhikary, vice president of marketing at ClioSoft. “Design teams are getting larger and are distributed over several locations, which leads to organizational and communication-related issues. In addition, designs no longer start from scratch. They rely heavily on design re-use and external IP, creating various challenges in combining data from different sources. And finally, design layouts are getting more complex with various tools, spanning all stages from specification, circuit design, logic design synthesis to layout and physical verification. Tracking the data and ensure its consistency is getting increasingly difficult.”

Conclusion

The next wave of cars will literally be data centers on wheels. They will need to employ many of the techniques for managing data that cloud companies now utilize, along with some unique ones that are specific to the automotive segment.

For chipmakers, and the entire chip ecosystem, this is both an opportunity and a challenge. Data centers operate servers in temperature controlled rooms with restricted network access. Cars sometimes operate in harsh conditions, and any bottleneck in traffic can result in an accident rather than a spinning wheel on a computer screen.

Normally, this kind of technology would take years of development and testing to roll out, but with some autonomous features already on the road, carmakers are accelerating this technology. The big question now is whether the data can keep up, and for how long.

This article was originally published on www.semiengineering.com and can be viewed in full

(0)

(0) (0)

(0)Archive

- October 2024(44)

- September 2024(94)

- August 2024(100)

- July 2024(99)

- June 2024(126)

- May 2024(155)

- April 2024(123)

- March 2024(112)

- February 2024(109)

- January 2024(95)

- December 2023(56)

- November 2023(86)

- October 2023(97)

- September 2023(89)

- August 2023(101)

- July 2023(104)

- June 2023(113)

- May 2023(103)

- April 2023(93)

- March 2023(129)

- February 2023(77)

- January 2023(91)

- December 2022(90)

- November 2022(125)

- October 2022(117)

- September 2022(137)

- August 2022(119)

- July 2022(99)

- June 2022(128)

- May 2022(112)

- April 2022(108)

- March 2022(121)

- February 2022(93)

- January 2022(110)

- December 2021(92)

- November 2021(107)

- October 2021(101)

- September 2021(81)

- August 2021(74)

- July 2021(78)

- June 2021(92)

- May 2021(67)

- April 2021(79)

- March 2021(79)

- February 2021(58)

- January 2021(55)

- December 2020(56)

- November 2020(59)

- October 2020(78)

- September 2020(72)

- August 2020(64)

- July 2020(71)

- June 2020(74)

- May 2020(50)

- April 2020(71)

- March 2020(71)

- February 2020(58)

- January 2020(62)

- December 2019(57)

- November 2019(64)

- October 2019(25)

- September 2019(24)

- August 2019(14)

- July 2019(23)

- June 2019(54)

- May 2019(82)

- April 2019(76)

- March 2019(71)

- February 2019(67)

- January 2019(75)

- December 2018(44)

- November 2018(47)

- October 2018(74)

- September 2018(54)

- August 2018(61)

- July 2018(72)

- June 2018(62)

- May 2018(62)

- April 2018(73)

- March 2018(76)

- February 2018(8)

- January 2018(7)

- December 2017(6)

- November 2017(8)

- October 2017(3)

- September 2017(4)

- August 2017(4)

- July 2017(2)

- June 2017(5)

- May 2017(6)

- April 2017(11)

- March 2017(8)

- February 2017(16)

- January 2017(10)

- December 2016(12)

- November 2016(20)

- October 2016(7)

- September 2016(102)

- August 2016(168)

- July 2016(141)

- June 2016(149)

- May 2016(117)

- April 2016(59)

- March 2016(85)

- February 2016(153)

- December 2015(150)